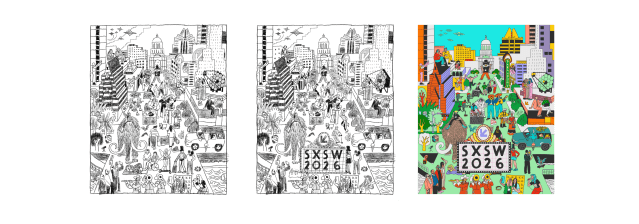

When he’s not transforming blank city walls on the streets of New York and Los Angeles into beautiful murals, illustrator Josh Cochran is creating vibrant, densely layered scenes for the likes of The New Yorker. His art celebrates the intersection of risk and play, imbuing a sense of good-natured chaos that makes city life feel electric.

SXSW 2026 marks 40 years of our homegrown event, and this year, we’re transforming downtown Austin into a global, week-long village for creatives and innovators that will spill out across the city. Every year, we commission an artist to help capture the zeitgeist of the SXSW year ahead, so naturally, Josh was the perfect fit. Now more than ever it feels like creatives and innovators need to be together to solve big problems and keep the fires lit when it feels especially chaotic.

We sat down with Josh to discuss the hidden easter eggs scattered throughout this year’s artwork, got his impressions of Austin culture (despite never having visited here), and learned more about his next big project.

SXSW: This is the first time in its 40-year history SXSW has ever featured people in its artwork. How did you approach that creative challenge?

Josh Cochran: The art directors sent me previous identities and they were all very graphic. I was encouraged to just go hard, play with all different types of people, body types—you know, people wearing suits and then weirdos in cut-off jorts. I was sent some reference folders with images and I also looked through the archive. I spent a lot of time just combing through and trying to get a sense of South by Southwest because I’ve never been. And the more I looked, the more I understood what they were looking for, which was this kind of eclectic, wild, party-festival that’s happening in the streets and also in the buildings and all over Austin. It was a fun challenge to try to figure out how to mash everything together.

The process has to have some element of risk to it; I have to feel a sense of danger in the drawing ...

So what was your starting point?

I began with the city scene, the one where you can see the Capitol building. I did a lot of research on Austin’s architecture and talked with the art directors about which buildings were important to include. Then I just started drawing from the upper-left corner and kind of let it grow out. I like to approach these really busy scenes and start with one thing and then add on to it…. like I’ll draw another person next to this person and see what the vibe is and then add another person and mess around with the colors a little bit.

Your pieces often feel busy and alive. How do you manage all that visual chaos?

The process has to have some element of risk to it; I have to feel a sense of danger in the drawing, if that makes sense. Just for it to be interesting, I think I can’t know how it’s going to turn out. And then I just would redraw a bunch of times. Each time I redrew it, I made it tighter and tighter.

How did you develop the color palette?

That was a journey. At first, my palette was much more subdued — sandy, limited, kind of quiet. I was just honestly encouraged to keep pushing. At a certain point I threw caution to the wind and I think that’s when it all sort of clicked; it just felt like a fit, the energy of the festival and the characters came more to life. Jann, one of the art directors, told me Austin’s actually quite green (I’d been picturing desert tones). So I started using this minty, cool green I’d been experimenting with in my personal work. I liked how it related to all the other colors and could complement skin tones, you know, or at least hint at skin tones.

In addition to people, there’s animals—both real and extinct. What’s the story with the woolly mammoth?

[laughs] Yeah, that was a request! They wanted something pre-historic, something unexpected. I’d never drawn a woolly mammoth before, so that was a first. But it was so huge and funny that it became a centerpiece. Someone even animated it later — I saw it on Instagram, with the peanuts moving in its nostrils. It was hilarious. Seeing other people interpret the work has been fascinating.

With any project I try to find some way to make it fun for me. Something to play around with or hide, or I have to figure out my way into it.

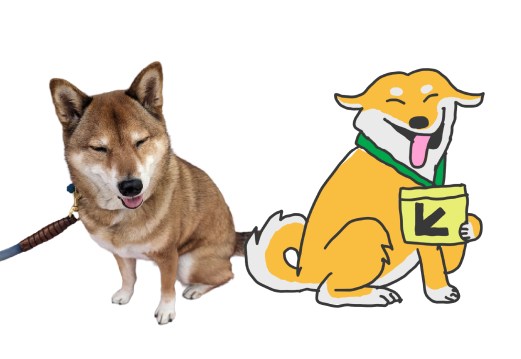

You’ve hidden personal touches in your work before. Did you sneak anything into this project?

You know, that’s my brother’s partner’s dog I snuck in. With any project I try to find some way to make it fun for me. Something to play around with or hide, or I have to figure out my way into it.

You’ve experimented with tattooing, too, right?

It was [during the pandemic] when people were learning how to bake sourdough bread. Tattooing was my bread making project. I had a former student that taught me—I went to his studio, and he let me tattoo him. And then I got all the supplies and my other studio mate went in on it with me. I think having my drawings, there’s a bit of a disposable quality working as an illustrator. You know I’ll do something for, like, The New Yorker or something and the next week it’s in the recycling bin. Tattooing is the complete opposite of that. It was really quite frightening and exhilarating. I recommend it for anyone that’s interested.

If you had to tattoo one piece from the 2026 artwork, what would it be?

There’s one guy that’s in the bushes, and I try not to make this person too creepy, but it’s kind of a creepy person in the VR headset. Something like that, and on a hidden part of the body could be fun.

Hard left turn out of handmade artistry, how do you see technology and AI changing illustration?

It’s completely upending everything in my world right now, for sure. Without a doubt. But I do feel fortunate because I’m in this in-between time – traditionally trained as an artist as well as quite comfortable working digitally.

It’s made me lean more heavily to the analog and also my hand. I’ve been getting a lot more work that’s more based on my own personal touch on things. Sometimes I struggled over parts of my career where I really wanted to make really clean things or things that were more perfect. Now I feel like I just have to fall back on my hand – drawing by hand, painting, getting messy. Having confidence in your hands is crucial. That’s what sets you apart now. I’m also seeing more demand for work that feels personal — things with my own touch, imperfections, quirks. People crave that human element again.

What’s your next project?

An 800-foot-long bicycle barrier for the NYC Department of Transportation in Harlem. The city’s sign-making machine will cut out [my] shapes into stencils, and then I’ll spray-paint them along the barrier.

Despite drawing it so well, you’ve surprisingly never been to Austin? What’s your review of our city looking at it through the prism of our archive?

Shocked. I was just like, Austin is a crazy place. Yeah, I just love the weird energy and all the people – the cowboy hats and, of course, the different animals, everywhere. It was just really, kind of a dream job for sure.